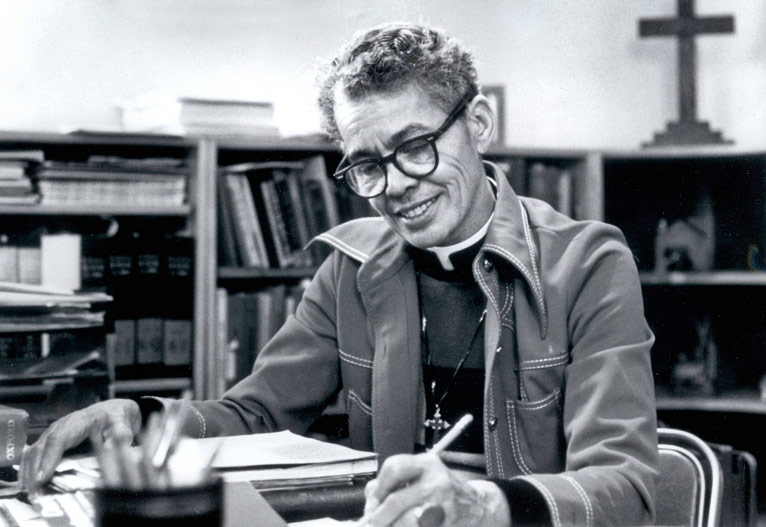

Murray College, the northern-most college sited closest to Science Hill, is named for scholar, lawyer, and civil rights activist Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray (1910-1985). Murray received a doctor of jurisprudence degree (1965) and an honorary doctor of divinity degree (1979) from Yale. An early leader of the civil rights and women’s movements, she was also a poet, writer, professor, and Episcopal priest. She is known for her lifelong commitment to challenging segregation and discrimination.

Early Life and Career

Born in Baltimore and orphaned at a young age, Murray was raised in Durham, North Carolina, by her aunt and grandparents. The descendent of enslaved African-Americans and slaveholding whites, Murray had strong ties to North Carolina and a deep commitment to her family. Yet from an early age, she wanted to escape what she called the “segregated pigeonhole” of the South. After high school she moved to New York and attended Hunter College. The 1929 stock market crash and ensuing depression delayed her studies, but she graduated from Hunter in 1933.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Murray worked for a variety of causes aimed at fighting inequality, racism, and poverty, including for the Works Progress Administration and the National Urban League. In 1938, she applied to the University of North Carolina to pursue graduate studies in sociology. Although the Supreme Court ruled that year that state schools were required to provide graduate education to black as well as white students, Murray was rejected on the basis of her race. Largely working on her own, Murray corresponded with the university’s president, Frank Porter Graham, sending copies of their letters to the African-American press and imploring Thurgood Marshall and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to take her case. The university denied Murray admission, and the NAACP refused to represent her—a decision that was likely based on her “maverick” tendencies as well as questions about her gender and sexual identity.

Murray was committed to fighting segregation and discrimination from a young age. Segregation, she believed, was a “monster” that “must be rooted out of our national life.” In 1940, while traveling by bus to visit her family in North Carolina, she and a friend were arrested for refusing to sit in broken seats reserved for black riders. Jailed in Petersburg, Virginia, Murray drew on a vast network of friends and colleagues, including Eleanor Roosevelt, for help. Despite initial assistance from the NAACP, Murray’s case did not become a springboard for challenging the constitutionality of “separate but equal” in the courts. Instead, she and her friend served jail sentences for disorderly conduct.

Back in New York a few months after her arrest, Murray began working with the Workers Defense League, a team of lawyers appealing the conviction of Odell Waller, a Virginia sharecropper sentenced to death for killing his landlord. Waller claimed self-defense but was convicted of first-degree murder by an all-white “poll-tax” jury. In the course of working on his case, Murray met Dr. Leon Ransom, professor of law at Howard University, who encouraged her to apply to Howard’s law school. Yet despite the efforts of Murray, Ransom, and many others—including Eleanor Roosevelt—Waller’s appeals were rejected, and he was executed in 1942. The experience galvanized her commitment to study law.[1]

Murray entered the Howard University School of Law in 1941. She began to study Gandhi’s teachings on nonviolence more closely, and she organized and led sit-ins at whites-only eating establishments in Washington, D.C., training her fellow students in methods of civil disobedience she had learned in A. Philip Randolph’s March on Washington Movement. Although the sit-ins were successful in forcing at least some establishments to serve African-Americans, white newspapers refused to cover the protests, and Howard administration demanded that the students end their demonstration.

Murray understood these struggles as part of a much larger movement toward justice and equality. As she told her fellow protesters, “No matter what happens to you temporarily, whether you are served in a restaurant, or go to prison, or get slapped down, the resources of human history are behind you and the future of human society is on your side, if there is to be any human society in the future. You have nothing to lose and everything to gain.”[2]

After graduating first in her class—and as the only woman—from Howard in 1944, she applied to Harvard Law School. Despite her top grades and a letter from Harvard alumnus and United States President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Harvard denied her application because she was not “of the sex entitled to be admitted to Harvard Law School.” Undeterred, Murray moved to California and received a master of law degree from Berkeley the following year. In 1946, she was named a deputy attorney general in California, making her the first African American in the state’s attorney general’s office.

In 1951, Murray researched and wrote States’ Laws on Race and Color, a 746-page tome detailing segregation laws and practices throughout the country. Thurgood Marshall called it the “bible” for lawyers working on Brown v. Board of Education and other civil rights cases. From 1956 to 1960, she was an attorney with the prominent New York law firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton and Garrison. Then, in 1960, Murray moved to Accra to become a senior lecturer at the Ghana School of Law. But an increasingly repressive political climate imperiled her position, and she considered returning to the U.S. She applied to Yale Law School to pursue a doctorate and was accepted.

Murray’s time at Yale was a pivotally important period in her life. She told a friend that her first year, “while strenuous, has been one of the most significant of my entire career and, for the first time perhaps, I begin to see all the fragments of experience in a hectic life falling together.”[3] In 1961, while working on her thesis, Murray was appointed to the President’s Commission on the Status of Women at the behest of her longtime friend and mentor, Eleanor Roosevelt. Serving on the commission’s civil and political rights committee, she developed the novel approach of using the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to challenge discrimination on the basis of sex. Murray used this argument to advocate for a new litigation strategy that would expand women’s rights along the same lines used by the NAACP in its attack on segregation. Around the same time, she helped organize and participated in the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. And an influential memorandum she drafted, distributed to members of Congress as well as Lady Bird Johnson, helped ensure that “sex” was included in Title XII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Murray had long argued that discrimination on the basis of sex was similar to racial discrimination. As a law student at Howard, she first wrote about “Jane Crow” and the double challenges African-American women faced. After graduating from Yale, she and Mary Eastwood published “Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII,” in the George Washington Law Review, a critically important essay that drew parallels between racial and sex discrimination. In 1971, a young legal scholar named Ruth Bader Ginsburg read “Jane Crow” and used it in her successful Supreme Court case, Reed v. Reed, challenging sex discrimination. The argument was so important to her thinking that Ginsburg named Murray and Eastwood as co-authors on her Brandeis Brief. Meanwhile, Murray continued to work with lawyers and activists in the women’s movement. In 1966, she helped Betty Friedan found the National Organization for Women, and she served on the national board of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Murray was a gifted writer of prose and poetry. She published a collection of poems, Dark Testament and Other Poems, and two memoirs, Proud Shoes: Story of an American Family, which explored her mixed family heritage, and, posthumously, Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage.

Murray responded to setbacks and obstacles with a renewed sense of purpose. Reflecting on her work years later, she remarked, “In not a single one of these little campaigns was I victorious…In each case, I personally failed, but I have lived to see the thesis upon which I was operating vindicated and what I very often say is that I’ve lived to see my lost causes found.”[4]

Decades of Scholarship and Service

All her life, Pauli Murray valued both teaching and learning. From 1967 to 1968, she was a vice president at Benedict College in Columbia, South Carolina, leaving to become a professor at Brandeis University, where she earned tenure and taught until 1973. She pioneered new programs of study and was the first person to teach African-American studies and women’s studies at Brandeis. In 1971, she was named Louis Stulberg Professor of Law and Politics—becoming the first person to hold the chair named for the president of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union.

After decades on the front lines of the civil rights and women’s rights movements—causes she considered inseparable—Murray broke yet another barrier. She left Brandeis and entered General Theological Seminary to prepare for the Episcopal priesthood at a time when women were not allowed to become priests. Those conventions were also changing, and at the age of 67, Murray became the first African-American woman ordained as an Episcopal priest in a ceremony at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. After her ordination, she celebrated the Eucharist in the same church in North Carolina where her white slaveholding and black enslaved families had worshipped, albeit in different sections. Murray held a Bible given to her by her grandmother, born a slave, and spoke at a lectern donated in honor of her great-grand-aunt, who had owned her grandmother. Murray described her decision to join the priesthood as part of her commitment to “reconciliation as well as liberation,” in the tradition of Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.

In 1979, Pauli Murray was awarded an honorary doctor of divinity degree at Yale’s Commencement. In presenting this honor to her, President A. Bartlett Giamatti said, “Diligent scholar, gifted poet, respected lawyer and teacher, insistent prophet and faithful priest, you have nurtured the gifts of the spirit for the common good. You are an inspiration to those who seek the upward way for the soul and for society. Others have always followed after.”

In 1985, Pauli Murray died of cancer. She is buried in Brooklyn, under the same headstone as her friend and longtime partner, Irene Barlow. In 2016, the Murray family home in Durham, North Carolina, was designated a National Historic Landmark.

Further Reading

Azaransky, Sarah. The Dream Is Freedom: Pauli Murray and American Democratic Faith. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Bell-Scott, Patricia. The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016.

Finn, Anthony B., ed. Pauli Murray: Selected Sermons and Writings. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2006.

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009.

Mayeri, Serena. Reasoning from Race: Feminism, Law, and the Civil Rights Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Rosenberg, Rosalind. Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

[1] Oral History Interview with Pauli Murray, February 13, 1976. Interview G-0044. Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007) in the Southern Oral History Program Collection, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/G-0044/excerpts/excerpt_8640.html

[2] Quoted in Gilmore, Defying Dixie, 391.

[3] Pauli Murray to Lloyd Garrison, July 6, 1962, Pauli Murray Papers, Schlesinger Library, Box 20, Folder 432.

[4] Oral History Interview with Pauli Murray, February 13, 1976. Interview G-0044. Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007) in the Southern Oral History Program Collection, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/G-0044/menu.html