Event Details

On September 14, 2023, Yale University and Divinity School will honor the Rev. James W. C. Pennington ’23 M.A.H. and the Rev. Alexander Crummell ’23 M.A.H. In the mid-nineteenth century, the Reverend Pennington and the Reverend Crummell audited classes at Yale Divinity School. As Black men, they were allowed to sit in class but not to matriculate, access library resources, participate in class, or earn their degrees. Despite these injustices, both went on to become noted pastors and leaders. In April 2023, the Yale Board of Trustees voted to confer on them the M.A. Privatim degrees to recognize their work and honor their legacies. Read the university statement that first announced this event.

Event

4 to 5 p.m.

Battell Chapel

400 College St.

New Haven, CT

View event page

RSVP for this event at opac.media@yale.edu.

Notes for journalists attending the event

Journalists should pick up badges at OPAC, 2 Whitney Ave. 3rd floor, Suite 330, 2 Whitney Ave. For more information, email opac.media@yale.edu.

Journalists should enter Woolsey Hall via the door on Hewitt Quadrangle closest to Woodbridge Hall. Staff will be on hand to escort you to your seat.

Backpacks and bags 12” x 12” or larger in size are not permitted at the event and reception, and Yale security staff cannot hold bags for guests. All bags are subject to search. Bag inspections will occur outside Battel on the slate area. Please allow ample time to arrive at the event and enter via Phelps Gate and walk down the path to the three doorways into Battell Chapel.

Biographies

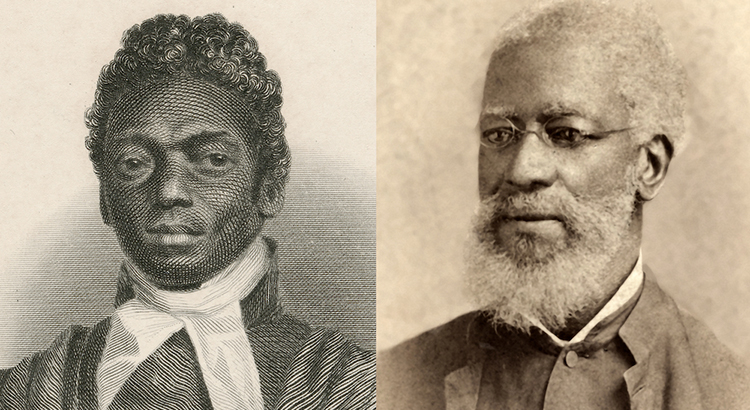

James W. C. Pennington

James W. C. Pennington, who liberated himself from slavery as a young man, became the first African American known to study at Yale. He was barred from formal enrollment and not permitted to speak in class, but still managed to use what he learned at the Yale Theological Seminary (later the Yale Divinity School) to thrive as a renowned pastor, respected civic leader, and leading abolitionist. Seeking to educate the public about Black history and slavery, Pennington in 1841 published A Textbook of the Origin and History of the Colored People, which scholars have described as the first textbook devoted to the history of African Americans.

Pennington was born enslaved in 1807 on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. In an 1849 memoir, Fugitive Blacksmith, he recounted the horrors he endured as a child. He had little contact then with his parents as they toiled on the plantation, and he often suffered from hunger. “To estimate the sad state of a slave child, you must look at it as a hopeless human being thrown upon the world without its natural guardians,” he wrote. A turning point occurred when Pennington witnessed a savage whipping of his father, Bazil: “Although it was some time after this event that I took the decisive step [to escape]… in my mind and spirit, I was never a Slave after it.”

Pennington fled the plantation in the fall of 1827. “Hope, fear, dread, terror, love, sorrow, and deep melancholy were all mingled in my mind together,” he recalled. Captured on a road outside Baltimore, he managed to flee again. The 19-year-old fugitive made his way to Pennsylvania, where he was welcomed into the home of Quakers William and Phoebe Wright. William began to teach Pennington how to read and write. Eventually, Pennington found his way to New York City. He continued his education and became a schoolteacher on Long Island.

“Hope, fear, dread, terror, love, sorrow, and deep melancholy were all mingled in my mind together.” ~James W. C. Pennington

Pennington then had an epiphany that he “was a lost sinner, and a slave to Satan.” He resolved to become a Christian minister, and that pursuit led him in 1834 to New Haven, where he sought enrollment in the Theological Seminary. He did not meet Yale’s entrance requirements and was, in any case, barred from enrolling according to a Connecticut law forbidding the instruction of Blacks from out of state—a law passed in the wake of a vote at an 1831 New Haven town meeting to prohibit the establishment of the nation’s first college for Black men. Pennington was allowed to attend—but not participate in—Yale classes. He began on Oct. 1, 1834, and continued to attend classes for at least two years. In an 1851 lecture in Scotland, covered in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, he described his time at Yale as his “visitorship” and catalogued the “oppression” he faced, including that he “could not get a book from the library, and my name was not to appear on the catalogue.”

Over the course of his career, Pennington served at Congregational churches in Connecticut, New York, Maine, Florida, and Mississippi. He raised funds to support the Amistad captives while pastor at the First Hartford Colored Congregational Church. (Now known as Faith Congregational Church, a Bible he used there is currently on loan to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.) In 1838, he presided over the wedding of Douglass, a fellow escapee from slavery—before the latter became a powerful and celebrated Black abolitionist—and Anna Murray. After becoming pastor at Shiloh Presbyterian Church in New York City in 1848, Pennington launched a campaign against the segregation of the city’s trolley services. The following year, Heidelberg University in Germany awarded Pennington an honorary doctorate. During the Civil War, Pennington helped raise a regiment of black soldiers to fight for the North. After the war, he served briefly as a minster in Natchez, Mississippi, in the heart of former slave country. He died in October 1870 while serving as a pastor in Jacksonville, Florida.

For further reading:

The Fugitive Blacksmith, by James W.C. Pennington

American to the Backbone: The Life of James W.C. Pennington, the Fugitive Slave Who Became One of the First Black Abolitionists, by Christopher L. Webber

Alexander Crummell

Alexander Crummell, an Episcopalian priest and scholar who battled racism throughout his life and came to espouse a pan-Africanist ideal, attended Yale Theological Seminary (later the Yale Divinity School) in the 1840s. Little is known about his time at Yale, but it seems that like James W. C. Pennington, he was not allowed to speak in class, use the library, or graduate with a degree. Crummell still made the most of his education as he became an original thinker and influential speaker who late in life founded the American Negro Academy, dedicated to Black uplift and self-improvement as part of a wider effort toward racial equality.

Crummell’s father, Boston Crummell, “was stolen from the neighborhood of Sierra Leone about the year 1780,” according to an 1866 article in Harper’s Weekly, and his mother was born free, living amongst a family of Quakers. Alexander was born in New York City in 1819 and attended a school established by the Manumission Society, an organization of wealthy Whites including Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. Crummell then attended Canal Street High School, founded by his father and other prominent people of color. “The black schoolchildren, who were jeered in the streets and pelted with stones, often had to be escorted to and from school by their parents,” writes Crummell biographer Wilson Jeremiah Moses.

In 1835, hungry for more education, Crummell traveled to Canaan, New Hampshire, to attend another abolitionist school, but a racist mob “assembled with 90 yoke of oxen, dragged the Academy into a swamp, and a few weeks afterward drove the black youths from the town,” he later recalled. Crummell then attended yet another school for non-White youth in Whitesborough, New York. Nevertheless, because of the color of his skin he was denied entry to the General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church.

Because the White American mind “revolts from Negro genius,” Crummell argued, “the Negro himself is duty bound to see to the cultivation and fostering of his own race-capacity.” ~Alexander Crummell

Undeterred, Crummell found Episcopalian supporters in Boston, and around the same time moved to New Haven to study at the Yale Theological Seminary. After completing his time at Yale, Crummell was ordained a deacon in St. Paul’s Church, Boston, and then a priest in St. Paul’s Church, Philadelphia, where he continued to face racial prejudice. From 1848 to 1853, Crummell lived in England, where he lectured, raised money for his then-parish, The Church of the Messiah in New York, and was offered a place to study at Queen’s College, Cambridge. After more than three years of study, he attained his B.A. and traveled as a missionary to West Africa, becoming a citizen of Liberia. He led a high school there, then became a professor at Liberia College in Monrovia.

Throughout his career Crummell was an outspoken activist who promoted Black self-help. Because the White American mind “revolts from Negro genius,” he argued, “the Negro himself is duty bound to see to the cultivation and fostering of his own race-capacity.” He decried Christian hypocrisy on the issue of slavery, and often urged Black emigration to Africa to help in what he called “the regeneration of that continent.” A central theme, as noted by Harper’s Weekly, was “that the colored man, then shut out from a worthy career in Europe and America, has a promising future before him in Africa, where he has been called to meet the demands of civilization, commerce, and nationality.” Yet after roughly 16 years in Liberia, political and social unrest spurred Crummell to return to the United States. Settling in Washington D.C., he founded St. Luke’s Episcopal Church and taught at Howard University. In the penultimate year of his life, he founded and became the first president of the American Negro Academy. Crummell died in Point Pleasant, New Jersey, in 1898.

For further reading:

Africa and America, by Alexander Crummell

Alexander Crummell, A Study of Civilization & Discontent, by Wilson Jeremiah Moses.

History of the MA Privatim

In the nineteenth century, the board of trustees awarded this honorary master’s degree to individuals who were unable to complete their studies due to special circumstances. That historical context has resonance for honoring the Rev. Pennington and Rev. Crummell, two visionary leaders who studied at Yale and took bold action in the face of unrelenting racism during the nineteenth century.